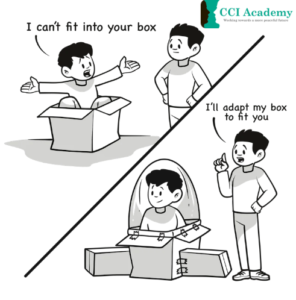

When mediators and coaches first learn how to mediate or coach, they are often taught a particular process with step-by-step instructions. This gives them a framework to follow as they practice and develop their skills. However, rigidly following those frameworks in the long term is likely to be problematic. Firstly, it may indicate that the practitioner is not learning and growing. Secondly, a lack of flexibility can lead to clients being disadvantaged – one size does not fit all.

I’m not saying that we should not teach a step-by-step process to beginner coaches and mediators. These can be helpful starting points for practitioner development. I like to use the analogy of learning to play scales in music. These scales are useful to refine our understanding of different keys, and our skills in hitting the right notes in order. However, a scale, in itself, is not very inspiring. Musicians need to know how to use those notes in various ways to make music. They can also mix and match those notes to adapt to various genres. However, you can’t just do this ad hoc or you end up with something that doesn’t sound very musical at all. There are still some frameworks and guidelines within which those notes can be used.

Similarly, many of the step-by-step processes we learn in mediation and coach training are not very inspiring “out of the box”. While they may be suitable for basic situations with some kind of standard or generic client (assuming there is such a thing!), chances are that there will be many situations in which an adaptation or more flexible approach is more appropriate. Standardised processes cannot provide long-lasting solutions for wicked problems. However, we need to be careful about what and how we adapt – an ad hoc approach is likely to create confusion and inconsistencies.

Purpose drives practice

To be able to tailor our “box” to fit specific clients, situations, or contexts, we need to understand the purpose of our process, and the purpose of the various steps and interventions within it. Then we can ask ourselves whether there might be different ways to achieve those purposes.

It’s also essential that the practitioner considers any adaptions from the client’s perspective. Discussing with the client their needs and concerns about the process, not just the substance of their conflict, prior to any service provision, will ensure that the practitioner is best placed to tailor a process that meets the client’s needs. This principle of co-design is essential for a truly client-centered practice.

Co-design is often presented as an important tool for working with those who have suffered trauma, neurodiverse clients, and to adapt to cross-cultural contexts. However, it does not need to be limited to those client groups. Co-design is an important tool to support self-determination for all clients.

What is co-design?

At its simplest, co-design means working with your clients to design a process that best meets their needs. Co-design is based on principles of empowerment, collaboration, creativity and capacity building. Approaches include shared decision making, iterative and flexible processes, and building sustained client engagement.

Co-design is more than just giving clients options, although that can certainly be a part of it. Meaningful engagement involves supporting clients to suggest and explore their own options, valuing their personal needs and lived experiences as informing what is likely to work for them.

Co-design in conflict resolution

While mediators are generally good at supporting clients to come up with their own options for substantive outcomes in a process like mediation, I wonder whether we might often miss the opportunity to co-design the process itself. This could include discussions about the structure and format of meetings, communication methods, decision making processes, and mechanisms for addressing power imbalances and ensuring fairness.

Questions for reflection

- What parts of your process do you see as not-negotiable? For what reason/s?

- Can you imagine situations / clients for which those aspects of your process could prove to be problematic? For what reasons?

- What parts of your process do you typically offer clients the opportunity to discuss adaptations? How do you do this?

- What other opportunities might exist for you to engage in co-designing a process with clients?

- What could be the impact of the system in which the codesign process will occur? How might that create support or resistance to codesign?

Pingback: Adapting our practice - Conflict Management Academy