The Australian National Mediation Accreditation System Practice Standards refer to power in a number of parts:

“A mediator must have knowledge [about] the dynamics of power and violence.” (Clause 10.1(a)(i))

“A mediator must be alert to changing balances of power in mediation and manage the mediation accordingly”. (Clause 6.1)

“A mediator must have the ability to manage power imbalances.” (Clause 10.1(b)(vi)).

However, it is arguable that in standard mediation training there is little time to explore the concept of power and its complex dynamics in any detailed way. Further, many experienced mediation practitioners and researchers have made the point that the language of “balancing power” oversimplifies a complex concept. Bernard Mayer goes so far as to argue that the concept of balancing power is a “confusing and possibly meaningless concept”.

In this article, I’ll provide a brief overview of the complexities of power and the problems with the concept of power balancing. I say brief, because in order to do this topic justice, it would take much more space than we have in this forum. I’ll be developing some additional resources on this topic later in the year, so if you are interested in more detail, please get in touch.

The concept of balancing power is based on some fundamental (and I suggest flawed) assumptions about power, its use, and what the mediator can do with it. The infographic below summarises the five main assumptions (and there may well be more):

What is power?

“We speak and write about power, in innumerable situations, and we usually know, or think we know, perfectly well what we mean. In daily life and in scholarly work we discuss its location and its extent, who has more and who less, how to gain, resist, seize, harness, secure, tame, share, spread, distribute, equalize or maximize it, how to render it more effective and how to limit or avoid its effects. And yet, among those who have reflected on the matter, there is no agreement about how to define it, how to conceive it, how to study it and, if it can be measured, how to measure it.” Steven Lukes, Power: A Radical View, 2nd Ed., p.61.

A common understanding of power is that A exercises power over B when A affects B in a manner contrary to B’s interests. When we talk about power in a mediation, this is often what we are referring to – our concern that one party might coerce another into agreeing to something that isn’t in their interests. While this is a worthy concern, in reality there are so many complicating factors that it is either impossible to know when this is happening, impossible to alter the situation if it is happening, or perhaps both!

Let’s consider some of the complexities:

A may not need to “exercise” their power in any conscious or intentional way for it to have an impact on B. For example, powerful people can induce deferential behaviour in others without any intention of doing so. Similarly, sometimes abstention or non-intervention (non-action) can be a form of power.

A may have power even if it is not used and has no impact on B. Power can be a capacity or a potentiality.

A’s power could potentially affect B in a manner that supports A’s interests.

A may have different sources of power (e.g. single issue power or multiple issue power) which will have different impacts in different situations. For example, A’s use of power in relation to topic X may mean that A forfeits any power they may have had over the remaining issues.

Power constantly intersects with context and perception, and it’s not always clear which is having the most influence on B (A, the context, B’s perception, or other factors combined).

Power exists on a spectrum, in fact multiple spectrums that interact and intersect with each other. As Steven Lukes explains, “we affect each other in countless ways all the time: the concept of power and the related concepts of coercion, influence, authority, etc. pick out ranges of such affecting as being significant in specific ways”.

A and B may be able to create power with each other. This is sometimes known as integrative power, or what Mary Parker Follett calls “power-with”.

It is difficult to identify a person’s interests and to evaluate whether and how B’s power may impact upon them. Everyone’s interests are multiple and conflicting, so it is hard to evaluate what is and isn’t in someone’s interests in any given situation. This is further complicated by what Steven Lukes calls the third dimension of power, which is the power to influence, shape or determine another’s interests (through the control of information, mass media, or socialization). People’s interests may be a product of a system which works against their interests.

Perceived uses and abuses of power are inherently linked to value judgements about legitimacy. How do we know when someone is “unfairly using power” to coerce someone to do something that is against their interests, as opposed to when someone is legitimately persuading someone to choose something that is not in their best interests, but may still be better than their alternatives. For example, compare the situation in which someone agrees to make significant concessions to the other party because they are afraid of violent consequences subsequent to the mediation if they do not do so and the situation in which someone agrees to settle a claim for which they do not believe they are liable in order to avoid the expense and adverse publicity that could arise if the matter proceeded to court.

Types of power

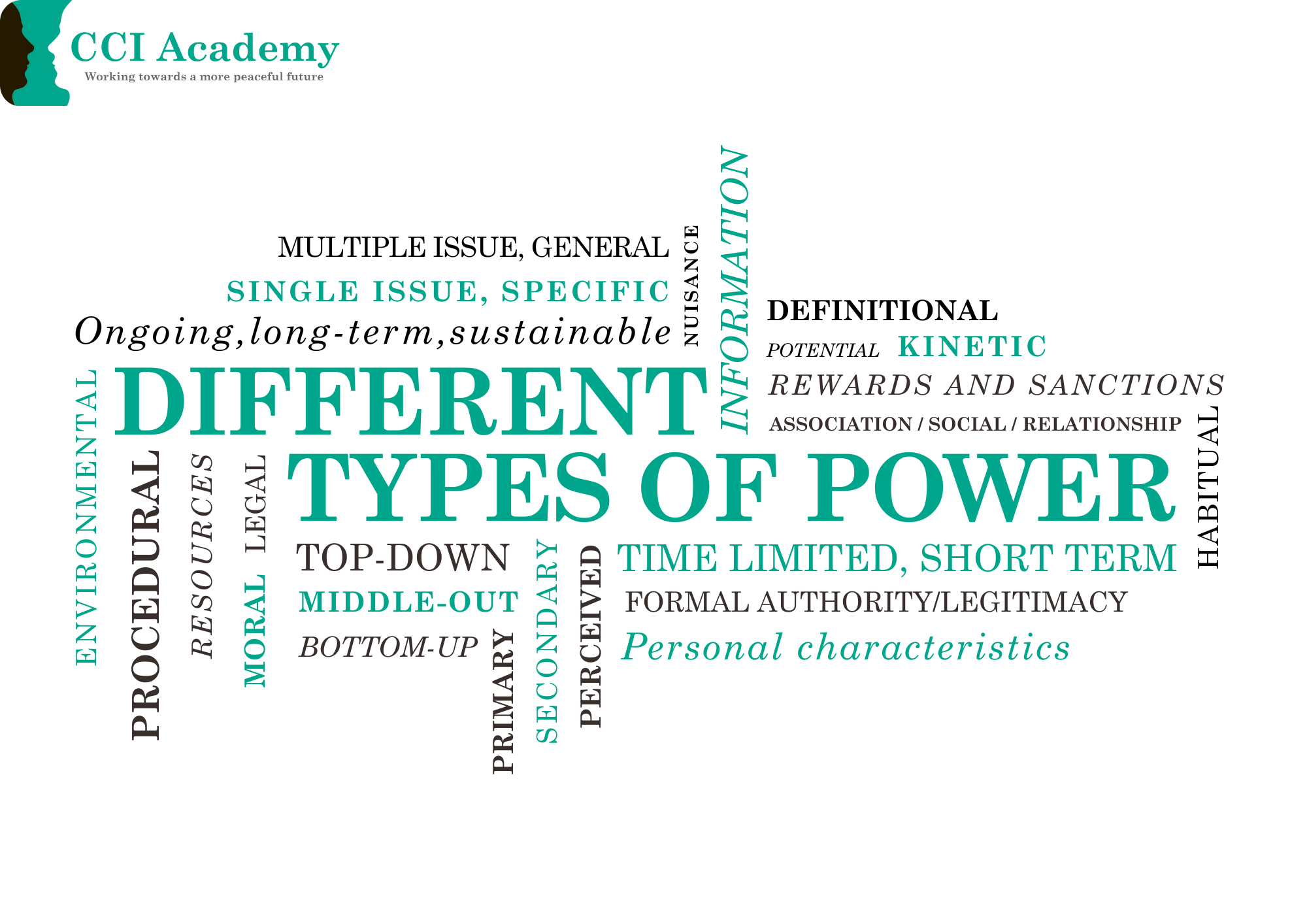

Power comes in all shapes, sizes, strengths, lengths of time, etc., etc. The following infographic shows a range of ways that power might show up (or not)!

Mediators’ influence on parties’ power dynamics

The reality is that mediators are not in a position to make judgements about who has power, whether or how any particular person might be using it, and the potential impact on others. They can only guess based on limited information and observations made during the mediation. Power doesn’t show up in stereotypical ways, and sometimes it isn’t visible at all.

There is also very little a mediator can do to “balance” power. The mediator may be able to control who speaks and for how long, and what kinds of things are discussed versus what topics are ignored or shut down. They may be able to control the process to some extent. However, it’s never clear whether that has any impact on power dynamics between the parties, and if so what that impact is in effect.

Even assuming that the mediator can have some impact on the power dynamics, this is likely to only be effective while the parties are in the room, and there could be significant risks in creating a false sense of security in the ‘weaker’ party which is then removed after the mediation ends.

A different way of thinking about power

I like Bernard Mayer’s idea of a different way of thinking about power in conflict. It actually has a lot in common with the transformative idea of the mediator’s role as supporting people’s sense of empowerment to interact in a constructive way in conflict.

“Instead of thinking that people need an equivalence or equality of power, we might more usefully think that people need an adequate basis of power to participate effectively in conflict.”

Bernard Mayer, (2012) Power and Conflict, Chapter 3 in The Dynamics of Conflict: a guide to engagement and intervention.

Some cautions about power for mediators

- Be careful not to misrepresent the mediator’s capacity to change power relationships.

- Be careful not to exacerbate the problematic nature of some power relationships.

- Be mindful that there may be sources of power that you do not notice, understand or agree with.

- Remember that people are influenced by power that exists in a culture / organisation / society. This may not be easily recognized or changed.

- Be mindful that sometimes, a mediator’s attempts at ‘balancing power’ can effectively be disempowering for all people involved (those who are perceived as the ‘weaker’ party as well as the ‘more powerful’ party).

Some essential reading about power for mediators

Hilary Astor (2005) Some contemporary theories of power in mediation: A primer for the puzzled practitioner. Alternative Dispute Resolution Journal 16: 30-39.

Morgan Brigg (2003) Mediation, Power and Cultural Difference, Conflict Resolution Quarterly 20(3) 287-306.

Peter T. Coleman (2000) Power and conflict, Chapter 6 in Peter T. Coleman and Morton Deutsch, eds., The Handbook of Conflict Resolution: Theory and Practice pp. 108-130.

Arghavan Gerami (2009) Bridging the theory-and-practice gap: Mediator power in practice. Conflict Resolution Quarterly 26(4): 433-451.

Deborah Gruenfeld (2020) Acting with Power: Why we are more powerful than we believe.

Tricia S. Jones and Ross Brinkert (2008) The power perspective, Chapter 6 in Conflict Coaching: Conflict Management Strategies and Skills for the Individual, Sage Publications.

Steven Lukes (2021) Power: A radical view, 3rd ed.

Bernard Mayer (1987) The dynamics of power in mediation and negotiation. Mediation Quarterly 16: 75-86.

Bernard Mayer (2012) Power and Conflict, Chapter 3 in The Dynamics of Conflict: a guide to engagement and intervention.

Bernard Mayer (2009) Using power and escalation, Chapter 6 in Staying with Conflict.